Debunking Dijkstra's “Toxicity”

15th April 2025 · By Aziz Iskandar

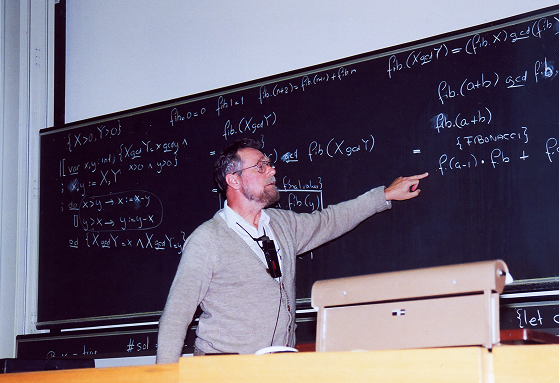

Say the name "Edsger Dijkstra" in a room of programmers, and you might get some knowing nods about groundbreaking algorithms, or perhaps some eye-rolls about his famous takedown of the GOTO statements. The rest might just mutter the common critique: "Brilliant, but kind of a jerk." What gets lost in these reactions is something far more critical than coding style or personality quirks: Dijkstra's urgent, ethical plea for deep understanding.

What made Dijkstra truly remarkable wasn't merely his infamous shortest-path algorithm nor his hatred of GOTO statements. It was his insistence that programmers must relentlessly pursue deep understanding. Every line. Every function. Every outcome. Not because it makes better code (though it does), but because anything less is an abandonment of ethical responsibility.

Yet, this ethical message is often drowned out. Sometimes, the nuanced ideas of other pioneers, like Alan Perlis's critique that Dijkstra's perfectionism ignores programming's inherently messy human element or Alan Kay's argument that Dijkstra's focus on correctness overlooks the importance of manageable interaction between components, are twisted to justify not digging deeper. "It's complex," we might say, echoing Kay's counterpoint to Dijkstra's formalism, but using it as an excuse to avoid mastering the complexity. "It's messy," we might admit, echoing Perlis's challenge to Dijkstra's rigidity, but without the commitment to clean it up through deep understanding.

This leads to the sarcastic jabs meant to shut down calls for discipline: "What next, you want me to build the CPU from sand?" or "Guess I'm not a real programmer if I didn't write my own OS from scratch." These are deliberate misdirections. Dijkstra wasn't demanding omniscience. He was demanding a commitment to understand your work at the relevant level, to know its boundaries, and to take responsibility for its behavior.

"Great scientist, bad people skills" is another convenient way to admire his algorithms while discarding his counter-intuitive ethical challenges. It's easy to write Dijkstra off as just another gatekeeper, completely detached from rapidly-evolving modern social reality. Obviously everyone wants to cheer for a freer, more inclusive coding culture, "Let people build however they want! After all, more coders should mean more innovation, more solutions, more progress…" right?

But, turning a blind eye to new problems isn't progress at all, it's actually regression in disguise. It is the inherent nature of progress for solutions to create new problems as old problems are solved. The rise of vibe coding without the accompanying drive to deeply understand isn't just a niche concern for programming purists. It's an existential issue for a society increasingly built on code, a new problem emerging from the rapid improvements of LLMs in the past few years. This isn't about programming purity. It's about survival – of businesses, of individuals, and ultimately of our increasingly digital society.

There's also a noticeable pattern: programmers who internalize Dijkstra's ethical demand for deep understanding often build more innovative and more reliable systems. This kind of craftsmanship tends to be valued, leading to greater professional success and economic reward. It requires continuous self-learning and accountability – traits often associated with a 'capitalist' work ethic focused on individual mastery and value creation.

Conversely, the pushback against this rigor sometimes carries a different philosophical undertone. The accusation that disciplined, successful programmers are just "capitalist dogs" hints at a resentment towards a system that rewards deep, individual expertise. The desire to make coding accessible to everyone (a worthy goal!) can get warped into an argument against demanding deep understanding, as if rigor itself is inherently elitist or anti-collective. This view might prioritize participation over mastery, sometimes viewing the relentless pursuit of individual understanding as selfish or unnecessary in a collaborative environment.

This creates a false dichotomy. Dijkstra's ethical call for understanding wasn't about hoarding knowledge or creating an exclusive club. It was about building a reliable, trustworthy digital world for everyone. Robust systems, built with care and comprehension, benefit society as a whole, underpinning economic stability and enabling collective progress. Shoddy work, born from a disregard for deep understanding, ultimately harms everyone, regardless of economic philosophy.

Dijkstra's core ethical message wasn't about specific programming practices. It was about the fundamental responsibility to understand what you create before, during, and after unleashing it to the world. The extinction-level threat isn't LLMs themselves. It's the culture that says understanding is optional. We need more programmers who, like Dijkstra, see deep understanding as an ethical imperative, not an optional luxury.

The key takeaway here is not to refuse to adapt to new technologies in a gatekeeping fashion, as some have mistakenly assumed was Dijkstra's point, but rather to embrace these advances while upholding our ethical responsibility to truly understand them. Let's welcome new programmers and new tools without abandoning the ethical core of deep understanding that Dijkstra fought for. In fact, as coding becomes more accessible, his principle becomes more crucial, not less.